[Do you have an ancestor whose story you’d like to discover? I am a professional genealogist with more than 25 years of experience. Find out how I can help!]

Vital records — births, marriages, and deaths — are essential in genealogical research, since they establish details about the major life events of an individual, including age, residence and relationships with parents, spouses and children whose names may not be found anywhere else. These vital records are typically created contemporaneously with the events they describe, either by the individual directly or by someone who knew them, often making them some of the most reliable records a genealogist has when proving identity and relationships.

Any genealogist who spends time studying their New York roots quickly comes up against one of the state’s most notorious blockers to research — vital records collection did not begin until 1881. For some researchers, the absence of vital records before this year prevents them from making any progress — something we genealogists call a “brick wall.”

Fortunately, this brick wall is surmountable. How, you ask? With probate petitions!

What is a probate petition?

“Probate petition” is a term used to describe a request filed in court by the executor of an estate (for a decedent who left a will) or an administrator of an estate (usually for intestate decedents) seeking permission to begin the process of settling an estate, such as through payment of debts and distribution of the decedent’s real and personal property. If a person left a will, the petition was called a petition to probate, and if a person did not leave a will the petition was called a petition to administer — genealogists refer to these collectively as “probate petitions.”

How does a probate petition help in New York research?

In 1829, the New York Legislature passed a new law with two requirements that are crucial for genealogists:

- Probate petitions had to name all heirs-at-law. This requirement was true whether or not the decedent chose to name an heir in their will, and it was true even if the decedent left no will at all.

- Estate papers had to be preserved. Previously, courts had free reign to discard papers related to the settlement of estates. Under the new law, courts were required to keep all probate papers on file.[1]

The 1829 requirement to name all heirs means that the names of family members, and their relationships to one another, can be learned by reading a probate petition, even in the absence of vital records. This is especially useful when no will was made, or when a testator omitted an heir from a will, either because the heir had received their inheritance during the testator’s lifetime, or because the testator had a dispute with the heir.

Places of residence were usually also given in a petition. If an heir was dead or was a minor at the time of probate, that was usually noted too.

Assuming the petitioner was truthful, all of this information can generally be expected to be likely complete and reliable, since it was given under oath — and all of it has been preserved by the courts, rather than discarded.

Compliance with the law began in 1830 and improved as time went on. This timing means some probate petitions can provide evidence of names, residences, dates and relationships for people born as far back as the early-1700s!

Who are Heirs-at-law?

In order to interpret probate petitions, the laws of inheritance in New York State need to be understood. In his book, New York State Probate Records, Gordon L. Remington provides a great summary:

Under the laws in effect in 1829, if a person left a will, they could leave their property to whomever they chose. In 1848, women in New York State gained the right to make wills, even if their husband was still alive. If a will was left, then it controlled inheritance.

In neither case was a person required to name any heirs at all, in which case rules for inheritance in intestate estates aid interpretation of the petition. According to Remington:

- children of the deceased received equal shares first;

- if a child was deceased, then that child’s issue received his/her parents’ portion;

- siblings inherited when a decedent left no direct descendants;

- half-siblings could inherit personal property, and real estate beginning in 1865. [2]

Anatomy of a probate petition

Let’s take a look at a probate petition and see what we can learn from it.

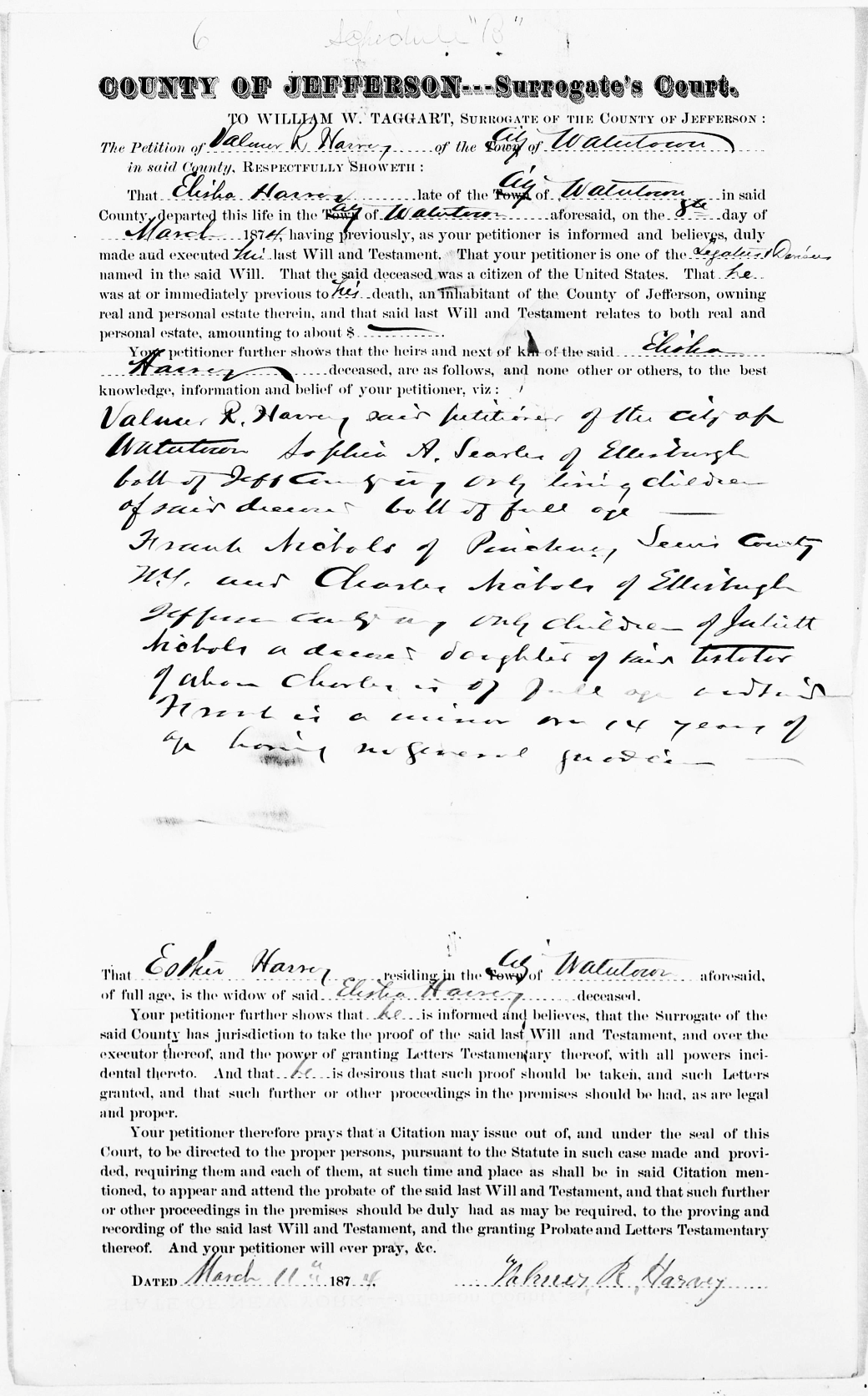

Below is the probate petition in the estate of Elisha Harvey, filed in the Surrogate’s Court at Watertown, Jefferson County, New York, by Valmer R. Harvey of Watertown. [3]

A reading of the petition provides a wealth of information:

- The opening names the petitioner, Valmer R. Harvey, and gives his place of residence as city of Watertown.

- Next, we learn the name of the decedent, Elisha R. Harvey, also of Watertown, and his date of death, 8 March 1874.

- We learn that Elisha was a U.S. citizen and was residing in the county immediately prior to his death.

- Next we learn that Elisha left a will and that Valmer was named in it as a legatee.

- We see the value of Elisha’s estate was not given, suggesting that an inventory of his personal belongings and a valuation of his real estate had not yet been conducted.

- Valmer next provides a list of all of the known heirs-at-law of Elisha:

- Valmer R. Harvey, himself, of Watertown – living son of majority age

- Sophia A. Searles of Ellisburgh – living daughter of majority age

- Juliett Nichols – deceased daughter

- Frank Nichols of Pinckney, Lewis County, New York – living grandson, a minor over 14

- Charles Nichols of Ellisburgh – living grandson of majority age

- Finally we’re told that Elisha’s wife, Esther, was still living and a resident of Watertown at the time of the petition on 11 March 1874.

We’ve learned a lot from one document! We now know Elisha’s exact date and place of death. We know that he had one son and two daughters in his lifetime, one of whom has died — and, crucially, we have learned the daughters’ married names! We’ve discovered the names of two of Elisha’s grandchildren, their relative ages, and their whereabouts. We’ve also learned the name of Elisha’s widow, though her relationship to the others in the petition is not stated and cannot be inferred.

All of the births, marriages and deaths described in this petition took place before New York State began collecting vital records in 1881, yet a careful reading has given us much of the information that vital records could have supplied.

Where to find probate petitions

Probate proceedings in New York State are normally filed with the Surrogate’s Court in the county where the decedent resided. Remington’s book provides contact information for each Surrogate’s Court in New York State. The earliest records may be at local or state archives.

Although some probate petitions are copied into will books, the originals are usually filed amongst the loose papers for an estate, commonly referred to as an “estate file” or “probate packet.” Remington’s book provides a comprehensive list as of 2011 of probate packet holdings at each Surrogate’s Court, plus an inventory of probate packets on microfilm at the Family History Library in Salt Lake City, Utah.

In recent years, both Ancestry.com and FamilySearch have placed probate records for New York State online.

Ancestry.com has not placed estate papers online, but some petitions may be found in the will books that they’ve digitized and made searchable in the following collections:

- New York, Wills and Probate Records, 1659-1999

- New York County, New York, Wills and Probate Records, 1658-1880 (NYSA)

FamilySearch is the only website that has digitized probate packets, as part of its online collection, New York Probate Records, 1629-1971. This collection has not been indexed for searching, so access is had by browsing the images manually.

The table I have compiled below indicates FamilySearch‘s online probate packet holdings for each county in New York at the time of this writing — remember that more may be available on-site at the Surrogate’s Court:

| County | Collection Name | Years |

| Albany | Probate records | 1868-1900 |

| Allegany | Estate papers | 1807-1930 |

| Bronx | none | |

| Broome | Probate records | 1846, 1876-1878 |

| Cattaraugus | index only | 1800-1956 |

| Cayuga | Estate papers | 1799-1905 |

| Chautauqua | index only | 1811-1962 |

| Chemung | Estate papers | 1836-1900 |

| Chenango | Probate records | 1809-1829, 1869-1883, 1885-1889, 1891-1912 |

| Clinton | none | |

| Columbia | Estate papers | 1830-1880 |

| Cortland | Estate files | 1810-1893 |

| Delaware | Estate papers, proceedings | 1797-1900 |

| Dutchess | Probates [date] packets | 1793-1868 |

| Erie | Estate papers | 1800-1929 |

| Essex | index only | 1799-1938 |

| Franklin | index only | 1800-1900 |

| Fulton | Probate records | 1877-1908 |

| Genesee | Probate records | 1856-1908 |

| Greene | Estate papers | undated |

| Hamilton | Estate papers | 1861-1908 |

| Herkimer | Estate papers | 1792-1900 |

| Jefferson | Estate papers | 1805-1945 |

| Kings | index only | 1780-1971 |

| Lewis | index only | 1805-1940 |

| Livingston | Estate records | 1822-1905 |

| Madison | Estate records | 1847-1875 |

| Monroe | index only | 1821-1970 |

| Montgomery | Probate records | 1874-1922 |

| Nassau | none | |

| New York | Miscellaneous probate records | 1800-1869 |

| Niagara | Probates | 1834-1970 |

| Oneida | Probate proceedings | 1867-1965 |

| Onondaga | index only | 1802-1923 |

| Ontario | Probate records | 1828-1924 |

| Orange | none | |

| Orleans | index only | 1825-1926 |

| Oswego | index only | 1846-1916 |

| Otsego | Petitions | 1929-1934 |

| Putnam | index only | 1812-1970 |

| Queens | index only | 1787-1987 |

| Rensselaer | Estate files | 1793-1906, undated |

| Richmond | none | |

| Rockland | Probates | 1802-1900 |

| Saratoga | Probate records | 1857-1885 |

| Schenectady | Probate records | 1871-1917 |

| Schoharie | index only | 1795-1902 |

| Schuyler | index only | 1855-1970 |

| Seneca | index only | 1804-1914 |

| Steuben | none | |

| St. Lawrence | none | |

| Suffolk | none | |

| Sullivan | none | |

| Tioga | none | |

| Tompkins | index only | 1818-1910, 1936-1951 |

| Ulster | Probate packets | 1707-1921 |

| Warren | Estate records | 1941-1955, undated |

| Washington | none | |

| Wayne | index only | 1823-1964 |

| Westchester | Estate papers | 1795-1900 |

| Wyoming | Petitions, probate records | 1841-1900 |

| Yates | none |

Final Thoughts

Probate petitions are a terrific substitute for vital records when you’re working on individuals and relationships in New York State before 1881. If you are lucky enough to find a probate petition, look closely and you may find the evidence you need to break down your brick wall.

Some probate petitions have been lost. If you cannot find a probate petition, don’t give up hope. Instead, check newspapers for the area in question — courts often required a petitioner to publish notices to heirs in the local newspaper of record for several consecutive weeks. A newspaper announcement may not be as comprehensive as the petition itself, but it will usually contain all of the names and residences, which may be enough to get you over that brick wall.

If a probate petition helps you break down your brick wall, please leave a comment so that other readers can benefit from your experience! Good luck!

Sources

[1] New York Genealogical & Biographical Society, New York Family History Research Guide & Gazetteer (New York: NYG&B, 2014), p. 65.

[2] Gordon L. Remington, New York State Probate Records: A Genealogist’s Guide to Testate and Intestate Records, Second Edition (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2011), pp. 28-29.

[3] Jefferson County, New York, estate papers file H-494, Elisha R. Harvey (1874), petition to probate, 11 March 1874; image, “New York Probate Records, 1629-1971,” images, FamilySearch (http://www.familysearch.org : accessed 2 May 2017) > Jefferson > Estate papers 1805-1900 box H 35-39, case 494-528 > image 4 of 1259; citing Jefferson County Surrogate’s Court, Watertown.

This short, concise information was perfect for me to follow up on NY ancestors. Thank you very much.

LikeLike

Nancy, thank you, I’m glad you found it helpful! Good luck in your research – Mark

LikeLike