[Do you have an ancestor whose story you’d like to discover? I am a professional genealogist with more than 20 years of experience. Find out how I can help!]

Thorp family sketch in Hardin’s 1893 History of Herkimer County [pg. 127, family sketches]

“Prof. Joshua Thorp, who spent most of his life in teaching…was for some time principal of the academy at Onondaga Valley, N.Y., and also of the High School at Watertown. He was a very successful teacher and lecturer, and was in the war of the Rebellion.”

So read a sketch of the Thorp family published in 1893 in Hardin’s History of Herkimer County, New York. By this account, Joshua Thorp led a rather illustrious life, excelling in the noble profession of teaching, serving his country during the Civil War and raising two children.

Yet, Hardin’s work was not entirely unbiased. Like many publishers of “glory books” in his day, Hardin probably partially paid for its publication by canvassing homes in the county, offering to include a person’s biography in exchange for their commitment to buy a copy. In this case, Hardin likely got his details from Joshua’s son John Jacob Thorp, who resided in the county.

John was busy building a business reputation of his own. Hardin needed a sale. Both had reason to tell a happy tale.

Was the story true? Read on and judge for yourself….

Fact or Fiction?

Joshua Thorp was born about 1825 in the Town of Root, Montgomery Co., in New York’s historic Mohawk Valley, a son of Ebenezer Deacon Thorp and Martha Ann Young.[1][2] By 1846 he and his wife, Catherine Shull, had welcomed their first child, Louisa Ann “Eliza” and three years later came son John Jacob.[3]

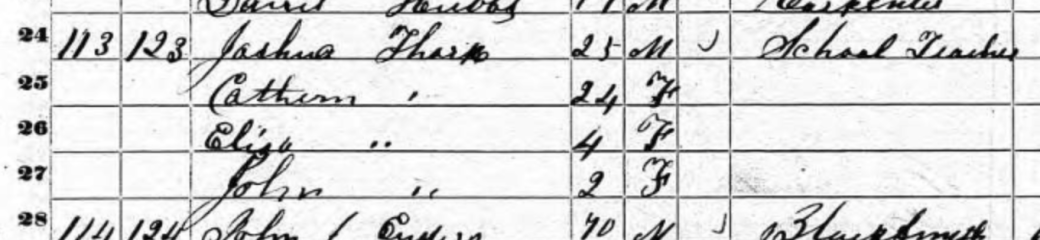

Joshua was indeed an educator. In the 1850 census (the first in which the whole family appears by name) Joshua reported his occupation as “school teacher” and he is on record as a teacher at the Crum Creek School in the nearby Town of Oppenheim.[4] As for whether he was principal at Watertown, records do not exist to investigate the claim[5]; however, an unbroken chronology of principals at Onondaga Valley Academy does exist and Thorp’s name is not on it.[6] ….Strike one.

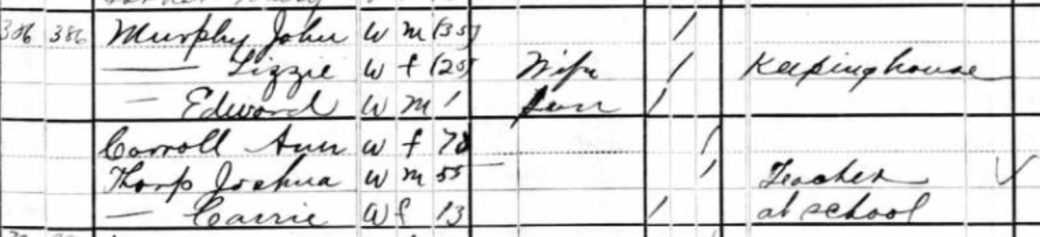

1850 census of Town of Root, showing Joshua Thorp employed as “school teacher.”

According to Hardin, Joshua also served in the Civil War; however, there are no records of a New York soldier by that name to support that claim.[7] ….Strike two.

Given the conflicting evidence, the verdict on the veracity of Hardin’s book is a mixed one. Joshua did indeed teach, but not where Hardin reported. And there is no evidence of a military career.

The true story of Joshua’s life would be found in other records—and in surprising places….

A Family Broken

In the summer of 1853, tragedy struck Joshua’s home when his 28 year old wife Catherine died, leaving him to care for his daughter Louisa, 7, and son John Jacob, 5.[8]

In the 1855 census, Louisa and John were living with their grandparents, Ebenezer and Martha, and their aunt Hope A. Thorp, on the family farm in Root.[9] By 1860, Ebenezer and Martha were both dead.[10][11] Joshua was not named in his father’s will.[12] By 1865, Louisa had married and John, 16, had been taken in by his uncle John I. Shull at his farm in the Town of Danube.[13][14]

Where had Joshua gone? Was he off looking for better paying work to provide for his children? Or had he abandoned them? The search for answers to these questions would lead far away from the family farm in New York….

Headstone of Catherine Shull, wife of Joshua Thorp.

Credit: Elizabeth Olmstead at Findagrave.com

A New Start

Joshua showed up next in 1861, 900 miles away in Stark County, Illinois, where he was teaching in the town of Toulin. According to Leeson’s Stark County history, “[Joshua] Thorp presided over the seminary from October, 1861 to February 1862….In March 1862, [he] proposed to teach the high school for $30 per month, on condition that he be authorized to employ a female assistant”[15] Leeson goes on to say “J. Thorp…was principal of high school, or No. 1, at $50 per month,”[16]

Why had Joshua left his children to teach in Illinois of all places? The records don’t say.

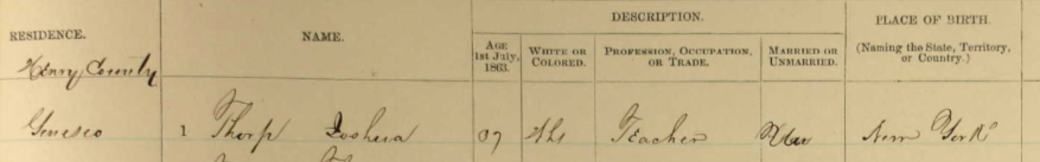

Joshua didn’t stay in Toulin for long. By 1863, he’d moved 40 miles northwest to Geneseo, Henry Co., Illinois, where in June he registered for the military draft. By this time, the country had been in a state of civil war for two years. He reported himself to be a 37 year old unmarried teacher born in New York. Was this proof of the Civil War service Hardin reported back in New York? As it turns out, no. There are no records of a Joshua Thorp serving from Illinois; in fact, there are no records fitting Joshua’s description serving from any state during the war. The claim of Civil War service, like the one about being principal at Onondaga Valley, seems to have been bogus.[17]

1863 draft register for Henry County, Illinois, showing Joshua Thorp.

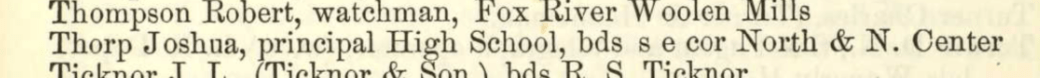

By 1867, Joshua had moved again, to Kane County, where he found work as principal of the high school at Elgin City, while boarding at a house on the southeast corner of North and North Center streets.[18]

1867 Kane County, Illinois, directory showing Joshua Thorp

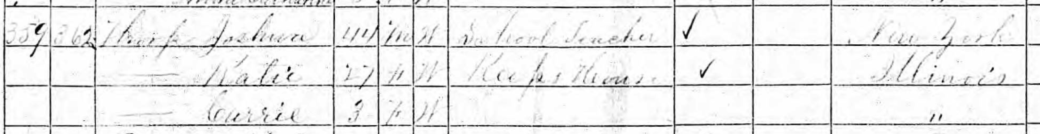

By 1870, Joshua had moved yet again—and this time he had company. The federal census of Polo, Ogle County, Illinois, shows Joshua, a 44-year-old school teacher from New York, living with wife Katie, a 27 year old housekeeper born in Illinois, and three-year-old Carrie Thorp, also born in Illinois.[19]

1870 census showing Joshua, his new wife, Katie, and their daughter, Carrie.

After years of moving around, Joshua began to put down roots in Polo. He was admitted to the local lodge of Freemasons and appears to have become a favorite. A newspaper article entitled “Masonic Festivals” tells of him reading the poem “Solomon’s Temple” and presenting a chair to one of his fraternal brethren “in a very happy manner, eliciting universal commendation.”[20]

Joshua had a new family. He was well-liked in his new community. Things were looking up for him, professionally and personally.

A Turn for the Worse

Joshua’s good fortune would not last long. Within a few short years tragedy struck again, when Katie died. The 1880 census shows Joshua as a widower and single father caring for Carrie, by then 13, and attending school. The two were boarding in the South Evanston neighborhood of Chicago where Joshua was employed as a teacher.[21]

1880 census showing Joshua as a single father once again.

By the time Carrie reached adulthood, Joshua’s life was crumbling.

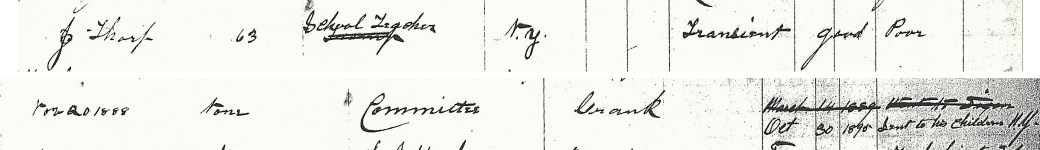

On 20 November 1888, “J. Thorp,” a 63-year-old schoolteacher from New York, was admitted to the Ogle County Almshouse at Oregon. He was listed as a “transient” with a “good” education, but in “poor” health. Joshua had apparently lost all means to support himself and he had no property to speak of. The cause for his “pauperism” was listed as “crank,” a term indicating he had become unbalanced, eccentric and ill-tempered.[22]

Ogle County Almshouse was locally known as the “County Farm,” since it was quite literally a farm. In 1878, the county Board of Supervisors had authorized the purchase of 50 acres along the west bank of Rock River, south of Oregon, and the erection of a building to house patients. In 1883, an 18-room brick building for the insane was also built. In Joshua’s time, the farm was expanded to over 100 acres. Not until 1909 were the buildings “heated with hot air furnace by blast, and lighted by electricity”[23].

Within a few months of admission, Joshua may have been transferred to the Elgin State Hospital, originally opened in 1851 for treatment of the insane. An entry in the almshouse register for Joshua reads “March 14, 1889 Went to Elgin,” but it is crossed out.[24] If he was sent to Elgin he may have been turned away (explaining the cross-out) since prior to 1894 Elgin’s policy was to send those who were too infirm for treatment back to their county’s almshouse.[25] This was probably the case with Joshua, who was in poor health.

Joshua was eventually discharged from Ogle County Almshouse on 30 October 1895.[26] In total, he had been a patient nearly seven years.

Upon discharge, Joshua was “sent to his children” in New York.[27] His destitute condition must have been quite a shock to his family and friends, who by then had in their hands Hardin’s glowing remarks about his achievements as a soldier and educator. This was not the man proud son John Jacob had described only two years earlier!

Entry for Joshua’s original admission to the Ogle County Almshouse.

Things must have gone badly for Joshua upon his return to New York since he didn’t stay long. Just five months later, on 27 May 1896, Joshua was readmitted to the Ogle County Almhouse in Illinois. The cause of his condition was again listed as crank. Authority for his admission was recorded as “returned from the east.”[28] Had he returned to the almshouse voluntarily or was he forcibly admitted? The record hints at the latter.

His second stay would be his last. Joshua Thorp’s life came to an end at the Ogle County Almshouse, when on 31 July 1900 he died of consumption (a.k.a. tuberculosis). He was 75 years old. He was laid to rest in the almshouse cemetery.[29]

The Final Insult

Dying at the almshouse wasn’t the last indignity the once-hailed professor would suffer—his headstone was even inscribed with the wrong name: Joseph Thorp.[30]

Joshua Thorp’s headstone in Oregon. Credit: Kris Gilbert

Adding insult to injury, due to a land dispute in 1967 all the markers in the almshouse cemetery were pulled up and piled in a corner near the road. It wasn’t until 1970 that the markers were put back, but by then no one was quite sure where each patient was buried, so the stones were laid flat on the ground in rows according to best guess.[31]

So for more than a century, Joshua Thorp has lain buried in a farm field, made nameless by a careless mistake, and today his actual resting place is only an approximation.

County Farm Cemetery, the field where Joshua Thorp is buried. Credit: Kris Gilbert

Unanswered Questions

For all the facts the paper trail reveals, the most important—and troubling—questions about Joshua’s life remain unanswered:

Why did he leave his children in New York? With all of his experience as a teacher and principal he clearly was capable of providing for them.

Hardin would have interviewed Joshua’s son John in 1893. By then Joshua had been a patient in the almshouse in Illinois a full five years. Is it possible that John hadn’t heard from his father in years and had no idea that he’d fallen on hard times? Or did John know and choose to leave that part out of the story he told Hardin in order to cover up his father’s tragic turn and his own embarrassment? Given the evidence contradicting Hardin’s book, it doesn’t seem too large a leap to conclude that John was giving Hardin the best story he could come up with about his father. A sterling family reputation would reflect well on John and his business. Who would bother traveling to Illinois to check the facts?

What kind of relationship did John and Louisa in New York have with their half-sister Carrie in Illinois? Perhaps none. Katie and Carrie weren’t included in Hardin’s account, indicating John never mentioned them. Likewise, in Illinois, Joshua’s obituary claimed he had “no relatives” surviving other than Carrie.[32] Did they not know about one another? Or was there acrimony amongst the children stemming from Joshua’s seeming abandonment of his first family years before? Certainly Joshua must have spoken to John and Louisa about his new wife and daughter during his brief return east in 1895. Then again, perhaps Joshua jumped the train en route and never made it back to New York at all.

Did Louisa and John ever find out what became of their father? Did they ever try to find his grave at the almshouse, only to be turned away? “Nope, no Joshua Thorp here.”

We’ll probably never know the answers to any of these questions, but thanks to diligent genealogical research we at least know the questions left to ponder.

Conclusion

This story began with the lofty claims of a son about his father’s grand accomplishments as reported to a publisher more than a century ago. Sound genealogical investigation proved essential parts of the story to be untrue—and left out—possibly out of ignorance, but just as likely to protect the family’s reputation.

Through careful evaluation of census records, city directories, newspaper accounts, almshouse registers and cemetery records scattered across nearly a thousand miles, the true story of Prof. Joshua Thorp’s life emerged, depicting a much more flawed—and perhaps sympathetic—character.

Would you like the story of your ancestor told? Read more about my professional genealogy research services!

Obituary for Joshua Thorp, printed in the Dixon Telegraph.

Author’s Note

The subject of this story was my great-great-great-grandfather. I’d like to thank two groups who made this story about him possible by pointing you to their websites:

First, are Kristine A. M Gilbert and the volunteers with the Ogle County, Illinois, GenWeb site. Kristine photographed and transcribed all of the stones at County Farm Cemetery in 2004 and put them online. Please have a look at Kristine’s work and if you have Illinois ancestors see the many other cemetery transcripts and photos created by the Ogle County GenWeb team of volunteers.

Second, are Ruth Abramovitz and Barbara Heflin with the Illinois Regional Archives Depository (IRAD), who transcribed the index to Ogle County Almshouse records and made them searchable online. Please read about their work on the IRAD website.

It was through the work of both these groups that I pieced together the final puzzle of who Joshua a.k.a. “Joseph” Thorp really was. Thank you!

Further Reading

If you’d like to learn more about using institutional records, including sanitariums, state hospitals, asylums, poorhouses and almshouses, as part of your genealogy research, then I suggest the article by Sharon DeBartolo Carmack entitled “Genealogy Workbook: Institutional Records,” published in the Jan/Feb 2016 issue of Family Tree Magazine. You can get it online or you can order a copy via interlibrary loan from your nearest library. [I provide the above link as a convenience to my readers; I’m not affiliated with Family Tree Magazine nor with the article author.]

References

[1] Hardin, George A., ed., History of Herkimer County, New York, Syracuse, N.Y.: D. Mason & Co., 1893, family sketches, 127; digital images, Internet Archive (http://www.archive.org : accessed 14 April 2016).

[2] Lethbridge, Melvin W. Montgomery County, N.Y. Marriage Records: Performed by Rev. Elijah Herrick, 1795-1844; also records of Rev. Calvin Herrick, 1834-1876; also records of Rev. John Calvin Toll, 1803-1844. St. Johnsville, N.Y.: Enterprise and News, 1922, p. 10, entry 350 for Ebenezer Thorp to Martha Young; digital images, Internet Archive (https://archive.org/details/montgomerycounty00leth : accessed 22 April 2016).

[3] 1850 U.S. census, Montgomery County, New York, population schedule, Town of Root, p. 654 (written), dwelling 113, family 123, Joshua, Catherine, Eliza and John J. Thorp; image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 14 April 2016); citing NARA microfilm publication M432, roll 533.

[4] “Crum Creek School” at Fulton County, New York, GenWeb (http://fulton.nygenweb.net/schools/Crumcreek.html : accessed 14 April 2016).

[5] An inquiry to the school district in 2000 indicated records were not available for time period in question.

[6] Slocum, Richard R. “In Old Onondaga Valley: The Academy and its Early Organization” at Onondaga County, New York, GenWeb (http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~nyononda/SCHOOLS/OVASJ.HTM : accessed 14 April 2016).

[7] Based on a search of military service records and pensions at Ancestry.com, Fold3.com, and FamilySearch.org for the name Joshua Thorp and variants in New York, accessed on 22 April 2016.

[8] Find A Grave, database with images (http://www.findagrave.com : accessed 14 April 2016), memorial 75501044, Catherine Sholl Thorp (1825-1853), Rockwood Cemetery, Rockwood, Fulton County, New York; gravestone photo by Elizabeth Olmstead.

[9] 1855 New York State Census, Montgomery County, population schedule, election district 1st & 2nd, Town of Root, unpaged, dwelling 150, family 25, for Ebenezer, Martha A., Hope A., Louisa and John J. Thorp; digital image, http://ancestry.com : accessed 14 April 2016); citing Census of the state of New York, for 1855. Microfilm. New York State Archives, Albany, New York (roll number not given).

[10] Find A Grave, database with images (http://www.findagrave.com : accessed 22 April 2016), memorial 37453511, Ebenezer Thorp (1792-1860), Rural Grove Cemetery, Rural Grove, Montgomery County, New York; gravestone photo by David Peck.

[11] Find A Grave, database with images (http://www.findagrave.com : accessed 22 April 2016), memorial 37453534, Martha Thorp (1798-1858), Rural Grove Cemetery, Rural Grove, Montgomery County, New York; gravestone photo by David Peck.

[12] Montgomery County, New York, “Book of Wills, Vol. 10” 544-546, Will of Ebenezer Thorp, 28 September 1860; digital images, Familysearch.org (http://www.familysearch.org : accessed 14 April 2016).

[13] Frasco, Jo Dee. “Marriage Records from the 1865 NY State Census, Town of Herkimer” at Montgomery County, New York, GenWeb (http://www.herkimer.nygenweb.net/vitals/herkmars1865.html : accessed 22 April 2016).

[14] 1865 New York State Census, Herkimer County, population schedule, Town of Danube, p. 11 (penned), dwelling 400, family 73, for Jacob I. Sholl (head) and John J. Thorp; image, http://ancestry.com : accessed 14 April 2016); citing Census of New York, for 1865. Microfilm. New York State Archives, Albany, New York (roll number not given).

[15] Leeson, M. A. Documents and Biography Pertaining to the Settlement and Progress of Stark County, Illinois. Chicago: M. A. Leeson & Co., 1887, 282; digital image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 14 April 2016).

[16] Leeson, p. 253.

[17] U.S. Civil War Draft Registrations, 1863-1865. Consolidated List, Class I, Fifth District, Illinois, Vol, 2, p. 709 (penned), entry for Joshua Thorp; digital images Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 14 April 2016).

[18] Bailey, John C. W. Kane County Gazetteer. Chicago: John C. W. Bailey, 1867, 203; digital images, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 14 April 2016).

[19] 1870 U.S. census, Ogle County, Illinois, population schedule, City of Polo, p. 46 (penned), dwelling 359, family 362, Joshua, Katie and Carrie Thorp; image, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 14 April 2016); citing NARA microfilm publication M593, roll 265.

[20] “Masonic Festivals.” Rockford Gazette (Rockford, Ill.), 6 January 1870, p. 6, col. 2; digital images, GenealogyBank.com (http://www.genealogybank.com : accessed 14 April 2016).

[21] 1880 U.S. census, Cook County, Illinois, population schedule, Village of South Evanston, enumeration district 217, p. 276 (stamped), p. 45 (penned), dwelling 386, family 386, Joshua and Carrie Thorp; image Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed 14 April 2016); citing NARA microfilm publication T9, roll 201.

[22] “Ogle County Almshouse Registers, 1878-1933.” Microfilm roll 30-2819, undated, unpaged, entry for J. Thorp with “Date of Admission” of 20 November 1888. Illinois Regional Archives Depository, Regional History Center, DeKalb, Illinois.

[23] History of Ogle Co., Illinois. Chicago: Munsell Publishing Co., 1909. 653; digital image Ogle County, Illinois, GenWeb (http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~ilogle/almshouse.htm : accessed 14 April 2016).

[24] see reference 22.

[25] “Elgin Mental Health Center” at Wikipedia.com (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elgin_Mental_Health_Center : accessed 21 April 2016); citing Briska, William (1997). The History of Elgin Mental Health Center: Evolution of a State Hospital. Crossroads Communications. p. 85.

[26] see reference 22.

[27] see reference 22.

[28] “Ogle County Almshouse Registers, 1878-1933.” Microfilm roll 30-2819, undated, unpaged, entry for J. Thorp with “Date of Admission” of 27 May 1896. Illinois Regional Archives Depository, Regional History Center, DeKalb, Illinois.

[29] see reference 28.

[30] Gilbert, Kris. “County Farm Cemetery, Oregon Township, Ogle County, Illinois” (http://www.kristory.com/CountyFarmCemetery.htm : accessed 14 April 2016). Photo of grave for “Thorp, Joseph.”

[31] “County Farm Cemetery, Oregon Township” at Ogle County, Illinois, GenWeb (http://ogle.illinoisgenweb.org/countyfarmcem.htm : accessed 14 April 2016).

[32] “Prof. Joshua Thorp Dead.” Dixon Evening Telegraph (Dixon, Illinois), 1 August 1900, p. 1, col. 3; digital images Newspapers.com (http://www.newspapers.com : accessed 21 April 2016).

You have ferreted a very intriguing story out of the records! That is my favorite part of genealogical research and I appreciate reading stories from others who are doing the same. I look forward to reading more from you in the future.

Best,

Melissa Finlay

LikeLiked by 1 person